Netflix’s Regency drama is now one of the most popular shows. The secrets to its success are explained by four writers – from colourblind casting and equal-opportunities undressing

1. Lanre Bakare: Christmas 1995 was a memorable one. I was sick and confined to the couch, eating mince pies and trying to stay hydrated as my sister sat down to watch Pride and Prejudice on VHS. A few years before, I was subjected to Jane Eyre’s Julian Amyes version starring Timothy Dalton. However, that was strangely gothic and unbeintentionally funny. This was another level.

Pemberley, Mr Bingley and Jennifer Ehle, with her bonnet. Colin Firth is in a pond. It was almost like water torture for an 11-year old who loved Rage Against the Machine and WWF. It was a horrible experience that made Austen and costume dramas seem like torture for me. I was disgusted by any sign of stiff-upper-lip, buttoned-down, non-sex-we-are-British Regency nonsense.

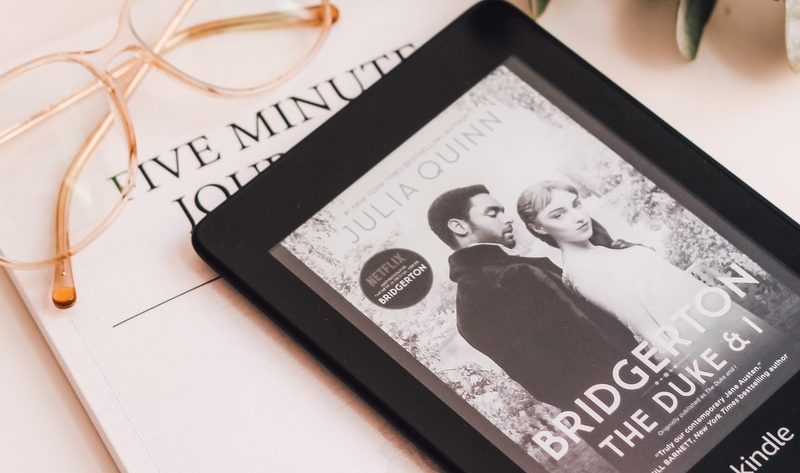

Then, 25 years later, Bridgerton turned up on Christmas Day. It is unapologetically savage and indulges in playing with the conventions of costume dramas. Infusing them with modern storytelling chops as well as the kind of extravagant production I saw last in Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette, it is unapologetically savage. This American-centric view of the Regency period focuses on the most popular aspects of British aristocratic tropes, such as the grandeur, pomp, and gilded enclosures. Although the repressed sexuality remains, it is countered by homoerotic boxing and unapologetically rampant bone-crushing.

The show is more than just sex and siring heirs. Bridgerton managed to get me interested in the logistical issues of 19th-century aristocrats. How can you deal with the fact that your daughters’ dowry has been wasted on unwise wagers? The townsfolk are horrified when the m’lady refuses a pig to be slaughtered. When you have a ball to go to, how about hiding the bump that indicates a future illegitimate? Daphne confronts her mom after she refuses to tell her about the intricate nature of the birds, bees. This is one of the most memorable scenes. Although it sounds absurd when written down, the Shondaland framing manages to make it interesting.

I don’t think I will be reaching for the Pride and Prejudice VHS any time soon, but Bridgerton has made me – and probably thousands of others – reconsider what a costume drama can be.

2. Jenny Stevens: Bridgerton is a romp in every sense of the word. The very first scene is where Daphne, the debutante, waits for her brother to take her to London. We then see him humping an opera singer against the tree, pants-at-knees. This is a lot of bottom in three minutes. You didn’t see this in Cranford. But then, you also didn’t get an orchestral reimagining Ariana Grande as a soundtrack.

This is the beginning of this modern period drama. This romantic comedy set in 1813 London feels very prescient of the current pandemic Britain. It’s courting season in Grosvenor Square. “Titled, chaste, and innocent” women rush into London to meet – or be forced upon, or laden with – a man who is a suitable male suitor. Potential matches are often held in public places with chaperones. Touching is prohibited. Although it isn’t exactly like meeting up with an Hinge or Tinder match to pretend that they are exercising, it doesn’t feel far away. It made me wonder if viewers will be able to see London’s singletons in knockoff Moncler duvets with woolly hair and Thermoses endure the socially distant park-bench dates in 2227.

Shonda Rhimes, Bridgerton producer, has quenched my thirst for drama and fluff in these difficult times. Her ability to balance the gaze of the audience on both the male and the female bodies has been a major plus. Rarely are there on-screen images of sex in which the men are dressed as casually as the women. This scene has more male tops than the 1994 Take That European tour. It takes some time to get used to the Viscount Bridgerton fully dressed.

As lockdown continues, and the lack of touch is felt more cruelly, Bridgerton, with its circus of gossip, secret trysts and drama, is a great balm for those who are at home alone and have a long winter ahead.

3. Poppy Noor: There is a TV rule that I follow. I will not watch a TV show if there aren’t people of color on it. This rule, despite its many advantages – I watch much less TV and can use it as an excuse to not watch many Judd Apatow films – has led me to believe that I don’t like period dramas.

This is a lie that I now realize is false. Bridgerton taught me that period dramas are something I enjoy – I was only put off by their near-total whiteness. Because of the universal themes that women are treated as doormats, period dramas should be able to appeal to all women. Ellen E Jones, a Guardian TV critic wrote that Fleabag is an example of art that can be attributed universality. However, this was based on the viewpoint of the dominant class. “Posh girls” is a shorthand for this. I’d add that almost all of these terms refer to “posh white girls”. This will help you understand why I haven’t been a fan of period dramas.

Who can resist the themes scandal, betrayal, and stupid men? These three themes are cleverly combined in Bridgerton with an element mystery: Lady Whistledown, a gossip columnist, informs high-society London (“the ton”) every week by mail. Everyone, including the viewers, wants to know her identity.

For a long time, there have been brown people in England (Cheddar man anyone?). But TV and film have always been content to whitewash history and fiction (e.g. James Bond).

Bridgerton would be absurd to call the highest level of representation. The characters of colour are not given the best treatment and have very little agency. His wife tricks the Duke of Hastings into marrying her and then into unprotected sexual relations with her. Some critics have labeled this as sexual assault. This is a clearer theme in the book than on the TV. He doesn’t want children. He tells her before they get married that he “cannot have” them. But she uses the power of the dictionary and insists she misunderstood his words, thinking he was impotent. She declares, “Cannot is different from will not!”

Marina Thompson, meanwhile is a beautiful, black woman sent to live in the Featheringtons’ home. She is the object of jealousy, scorn and finally revenge for her desire. In a nod towards the possibility that Queen Charlotte may have been mixed-race, an actor of color portrays her as Queen Charlotte. She pines for her mentally ill husband. Others have pointed to the fact that all of the love interests who are black are light-skinned. Lady Danbury is the only black character that you feel sorry for. She is, quite simply, the role model that you wish you had.

The show suggests that the king marrying a black woman removed racial inequalities in the 19th-century – which, well, you only have to look at what happened to Meghan and Harry in the 21st century to know that utopia hasn’t arrived. Race is rarely mentioned. It isn’t revolutionary to include a few words about people-of-colour in a show that features brown characters.

Bridgerton is a watchable, if not predictable. It would be a different show and I wouldn’t write about. To see people like me being allowed to star in a genre that is often closed off enticed me to explore a world I rarely get to see on the screen. Although I’m not of landed gentry, I am a person with colour and have never seen myself in period dramas (hats off to The Great). Although novelty may wear off, it is still a joy to see novelty on TV in your 30s.

4. Hannah J Davies: Bridgerton was my favorite. It was a mindless Regency spectacle that I loved. Bridgerton was a master of history, making the debate about The Crown seem trite and incoherent at a time when politicians are debating. The Downton approach was taken a step further by Bridgerton, who revelled in the anachronistic Taylor Swift and Ariana Grande string covers, Julie Andrews’ tattle-talking narration, and its diverse cast.

Like Gossip Girl – a 00s series getting the remake treatment – it is the kind of show you can consume while doing 100 other things or invest in fully to the detriment of your dinner (who cares about burnt fish fingers when you are pondering huge questions such as: “But will they? And is she pregnant?!”).

Executive produced by Shonda “Scandal” Rhimes, the puffy-sleeved hit has received the same criticism as some of her previous series, specifically that its “colour-blind” casting doesn’t hit the mark on race. It doesn’t, in truth. But it is like most TV in 2020. Bridgerton is a bit two-dimensional in terms of race. She’s more interested in visibility than reality. The whole period drama industry has much to offer when it comes moving white narratives out of the spotlight. It is unfair to criticize just one production or one creative of color. Its portrayal of sex in some places is also a bit “yikes”, but that’s not a major flaw in the hundreds or thousands of years of patriarchal nonsense.

Period dramas are not my favorite. I loved Saoirse Ronan’s memes shouting “I can’t!” more than I enjoyed Greta Gerwig’s lengthy adaptation of Little Women. I’ve only read one Jane Austen novel. I don’t even know which one. Even the words “Downton Abbey”, are enough to make me shiver – even before I consider how absurd Julian Fellowes’ writing. Bridgerton is an undoubted success. It is a heart. It is a mix of good and evil. It has Nicola Coughlan, from Derry Girls. It has once again made me happy to see a show that was set before 2000. This is a revision in history.